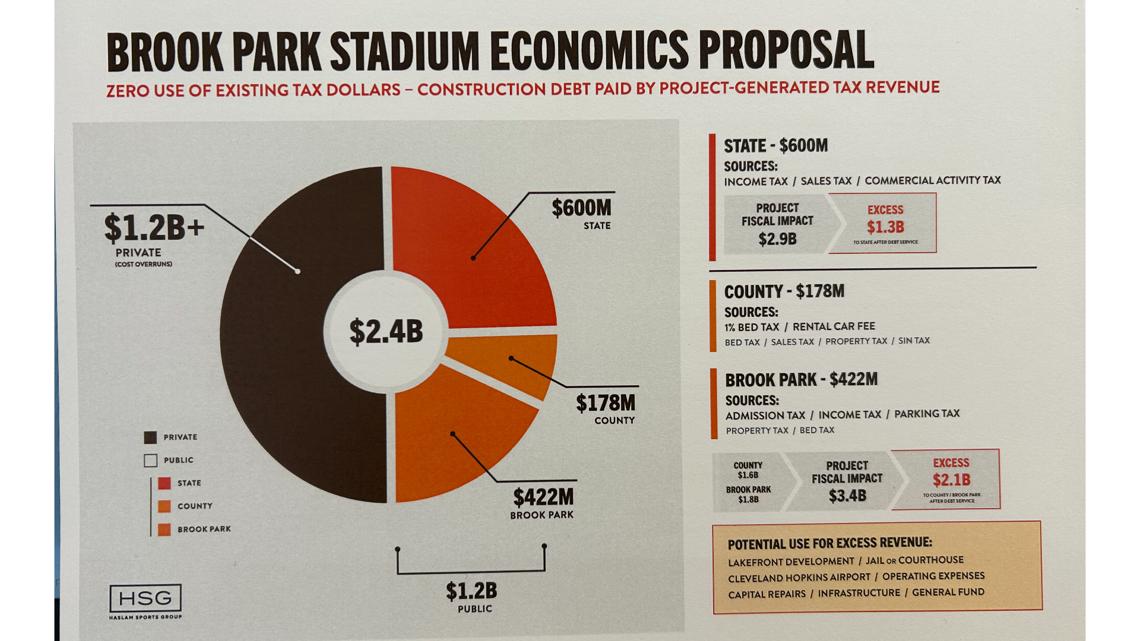

While the Haslams will contribute $1.2 billion, $600 million would come from the state of Ohio, $422 million from Brook Park, and $178 million from Cuyahoga County.

BEREA, Ohio — The Haslam Sports Group, owners of the Cleveland Browns, put forth its plan to finance the proposed $2.4 billion domed stadium in Brook Park during a meeting with reporters on Thursday.

The plan, utilizing a public-private partnership, calls the Haslam family to contribute approximately $1.2 billion for the new Huntington Bank Field, which would be ready for the Browns to use starting in 2029.

So how would the rest of the money be raised? The Haslam Sports Group says the public portion of the investment “doesn’t require any existing tax revenue and instead uses substantial new incremental tax revenue generated by the project itself.”

Here is a breakdown of the public funding plan:

CUYAHOGA COUNTY FUNDING – $178 MILLION

The Haslam Sports Group (HSG) says “the primary ask of the County is to leverage its strong credit and issue bonds that will be repaid by the new project-generated Brook Park revenues, along with two new county taxes on visitors to the region, the 1% incremental bed tax, and a rental car surcharge.”

The county would issue bonds generating $600 million in “up front project funding.”

“In our model, more than two thirds of the revenues backing the County bonds would be from new Brook Park sources, as approximately $422 million of the $600 billion would be attributed to Brook Park admission tax, incomes tax and parking tax, all generated by the project,” HSG explained in its outline.

The remaining $178 million would come from the bed tax and rental car surcharge.

BROOK PARK FUNDING – $422 MILLION

Saying that Brook Park has the potential to contribute nearly $1.8 billion in fiscal impact over its initial 30-year lease, the Haslam Sports Group proposes that the city’s admissions tax be increased from 3% to 6.5%, “generating substantial proceeds from Browns tickets and the other year-round activity enabled by the enclosed stadium.”

“Substantial income tax revenue from player and staff salaries, as well as development-generated labor, along with parking tax, also contribute to the project’s fiscal impacts and would be pledged towards funding for project costs,” the Haslams added.

The Haslam Sports Group says it is not asking the county for sales tax in its proposal due to the current plan to use a 40-year increase to help finance the $900 million Central Service Campus, featuring a new jail, in Garfield Heights.

STATE FUNDING – $600 MILLION

In the HSG plan, the other $600 million from public funds would come from the state of Ohio “in a new model that requires significant private investment, and only leverages the substantial new direct taxes generated within the project site to pay back the bonds.”

“We’ve worked to identify the net new incremental state income, sales, and commercial activity taxes from the project that will do more than just pay back the bonds, they will generate substantial excess for the State.”

What about Gov. Mike DeWine’s recent proposal to double the sports gaming tax in Ohio to 40% to help fund stadium projects statewide? The Haslams say while they were not part of the discussions, they do appreciate DeWine’s creativity and “look forward to learning more details about the plan while continuing to work on our proposal for state level support of this transformational project.”

Also, the Haslam Sports Group says that its plan solves “future capital repair needs.”

“Particularly if the County participates in the project and wraps the Brook Park revenue sources, the significant excess local tax revenues generated by the project will be more than sufficient to fund debt service on the bonds, capital repairs (projected to be approximately $400 million in future dollars over the life of the 30 year lease) and other public uses.”

THE IMPACT

HSG says its experts project $1.3 billion in annual economic impact from the stadium and the adjacent mixed-use development.

“Between the state and local levels, the project, together with Browns operations, are also projected to generate a total of $6.3 billion in fiscal impact/tax revenues over the life of the initial 30-year lease. At the local level, the project (and the additional proposed County taxes on visitors as well as a potential extension of sin tax) is expected to generate approximately $3.4 billion in fiscal impact/tax revenues,” HSG added.

The Haslams also say their funding plan will generate “significant excess new revenues over time” that could be used to support other important projects, including the downtown Cleveland lakefront development and the modernization of Cleveland Hopkins International Airport.

HOW WE GOT HERE

With the Browns’ lease at Huntington Bank Field set to expire in 2028, the Haslams announced in March of 2024 that they were down to two options when it comes to their future stadium site: a $1 billion renovation to the existing downtown stadium, or a domed stadium outside of the city at double the cost. Word soon spread that the Haslams had optioned more than 170 acres of land in Brook Park near Cleveland Hopkins International Airport.

On Aug. 1, in what the city called “a competitive deal to retain the Cleveland Browns at their current stadium site,” Mayor Justin Bibb put forth a $461 million financing proposal to the Haslams to renovate the 25-year-old facility. The plan included a 30-year lease arrangement.

Six days later, the Haslam Sports Group unveiled renderings and video showcasing what a domed stadium complex in Brook Park would look like. In a letter, Haslam Sports Group Chief Operating Officer Dave Jenkins referred to the idea of building $2.4 billion dome in Brook Park as a “transformational option” that will create “a modern, dynamic, world-class venue that would greatly enhance the fan experience and enable the State of Ohio and our region to compete for some of the biggest events in the world 365 days a year. Similar to other markets in the Midwest, this proposed domed stadium would catalyze our region in a major way.”

Less than a week later, Cuyahoga County leaders pounced on the proposal, arguing it “does not make fiscal sense” for citizens and taxpayers. County Executive Chris Ronayne urged the team to focus on renovating the current stadium, and stated that “any proposal that would create an unacceptable risk to the County’s general fund cannot be considered.”

On Oct. 17, the Browns confirmed their plans to move to Brook Park with an adjacent mixed-use development alongside the domed stadium. Team owners argued renovating the current stadium would not solve long-term issues, and that a domed stadium would allow them to host big events year-round and generate more revenue in the region.

In a press conference that same day, Bibb expressed his deep disappointment in the Haslam Sports Group’s decision, calling the team’s choice “frustrating and profoundly disheartening.”

“We have exhausted every single option to keep the browns in our city without compromising the general revenue of our city,” Bibb said during a press conference. “We remain committed to doing what we can to keep the Browns in Cleveland if Brook Park is not viable.”

One week after the announcement, the Browns filed a federal lawsuit asking a judge to declare the Modell Law, which requires any Ohio team playing in a tax-supported facility to give the city or locals the chance to buy the team, unconstitutional. Yost later filed a motion to intervene on the city’s behalf, which was granted. More recently, Yost and the city of Cleveland each filed motions seeking to overturn the Browns’ lawsuit.

In November, a Cleveland-commissioned study claimed Brook Park was not a viable option for the team. It found Brook Park would find it difficult to attract residents and retailers and also showed Cleveland would take a hit without a stadium, losing $30 million in economic activity and $11 million in tax revenue.

But a competing study commissioned by Haslam Sports Group found that while the move would close the door on the snowy types of home games, the Brook Park site would open the door to nearly 5,400 jobs and $1.3 billion in annual economic activity for Cuyahoga County.